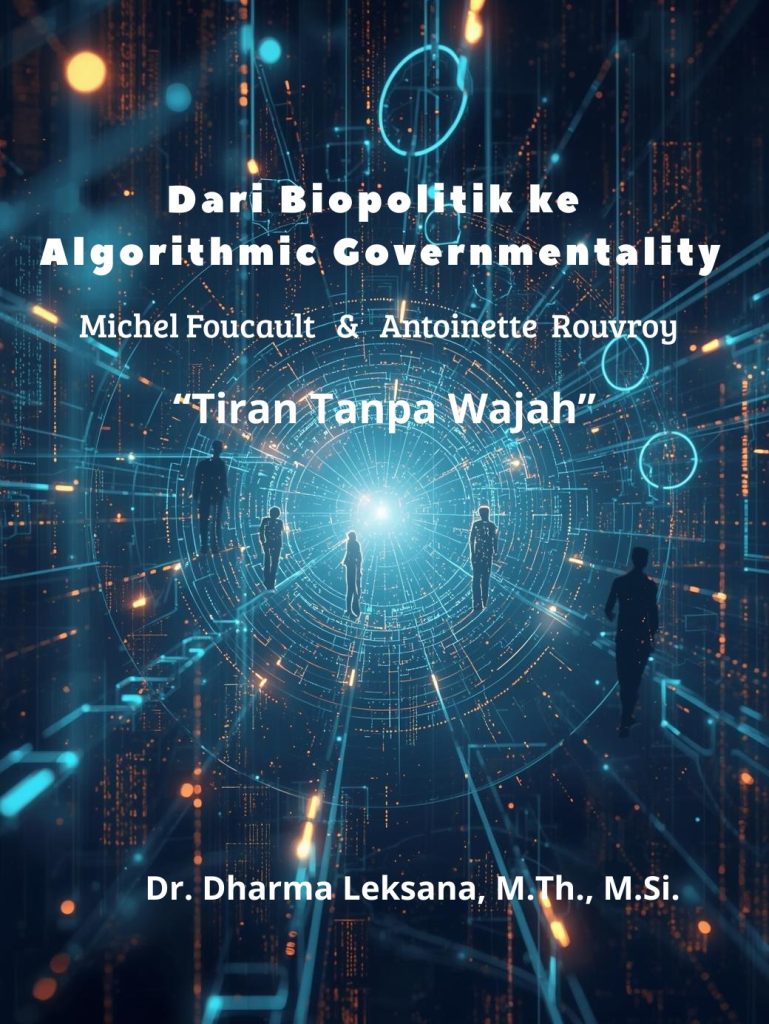

From Biopolitics to Algorithmic Governmentality: Reading Digital Power Prophetically

By: Dr. Dharma Leksana, M.Th., M.Si.

Introduction: Power Without a Face

We live in an era where every step, click, and screen tap leaves a trace. That trace is collected, analyzed, and used to predict our next move—sometimes before we even decide. Power in the digital age no longer appears as a ruler issuing decrees or police patrolling the streets. It appears as shopping recommendations, algorithms filtering our news, and scoring systems deciding whether we qualify for a loan.

This raises a pressing question: what does power mean in such an age? How can we understand it—and respond to it—critically? Two thinkers offer tools to answer this: Michel Foucault, who taught us to read the “biopolitics” of modern power, and Antoinette Rouvroy, who introduced the idea of algorithmic governmentality—a way in which algorithms govern without seeming to govern.

This article takes us from biopolitics to algorithmic governmentality and then one step further: toward a prophetic reading of these phenomena. Critique should not stop at academic analysis; it must also be a moral call—a summons to justice in the digital age.

Foucault: Power that Manages Life

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) was a French philosopher who refused to see power merely as oppression by rulers over the ruled. In The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1 (1978), he showed that modern power works more productively: it creates order, shapes habits, and manages life.

Foucault called this form of power biopolitics: power that focuses on managing human life. It works on two levels:

- The individual level (anatomo-politics of the body): bodies are trained, disciplined, and made productive—schools regulate schedules, hospitals set health standards, factories set rhythms of work.

- The population level (biopolitics of the population): states manage public health, birth rates, vaccination programs, sanitation—everything that affects collective survival.

Interestingly, this power is often voluntarily accepted. We obey because it seems reasonable: who would reject good health, orderly cities, and longer life expectancy? Foucault called this governmentality: the art of governing by getting people to govern themselves.

Rouvroy: Algorithmic Governmentality

If Foucault lived in the age of censuses and statistics, Antoinette Rouvroy writes in the age of big data. In her influential essays, she explains how power today no longer simply manages populations through numbers, but manages individuals through behavioral prediction.

This is what she calls algorithmic governmentality: the logic of governance executed by algorithms. Unlike law, which governs through prohibitions (“thou shalt not do X”), algorithms govern by nudging (“you might like Y”)—and we often follow these nudges without thinking.

Rouvroy describes this system as a “faceless tyrant”:

- There is no official consciously giving orders.

- There is no explicit malicious intent.

- Yet the decisions it produces—from credit scores to the ads we see to the videos we are recommended—shape the reality of our lives.

We live in an ecosystem where our future is calculated in probabilities, and our choices are guided by patterns machines learn from past data.

From Normalization to Prediction

One of Foucault’s key insights was the concept of normalization: how power shapes standards of what is considered normal, healthy, or acceptable. In the algorithmic era, this process of normalization becomes far more sophisticated.

Digital platforms collect billions of behavioral data points, then build statistical models of what is “normal” for someone like us. YouTube recommendations, Spotify playlists, and the ads we see on social media are ways in which systems nudge us toward behaviors predicted to please us—or to profit advertisers.

The result: we are no longer merely “legal subjects,” but data vectors. Our identity is read not from what we declare, but from our click patterns, locations, and watch durations. Our future is designed in the form of predictions—and those predictions often become self-fulfilling prophecies.

Social Implications: Guided Freedom

The shift from biopolitics to algorithmic governmentality carries serious ethical implications:

- Surveillance becomes invisible. CCTV cameras make us aware of being watched. Algorithms work silently: we rarely realize that the order of content we see is machine-curated.

- Control becomes individualized. State statistics operate on the level of populations; algorithms personalize every experience. Two people can inhabit entirely different digital worlds.

- Regulation becomes implicit. There is no explicit ban, just design that makes some choices easier and others harder.

Our freedom is not taken away by force—it is quietly guided. And because this process involves no obvious coercion, we seldom question it.

Prophetic Reading: From Analysis to Moral Call

This is where critique must go beyond academic description. Foucault and Rouvroy offer us the lenses to see, but we also need ears to hear the moral summons: Is this structure just? Who benefits, who loses?

In social theology, we speak of structural sin: injustice embedded in systems, not just individual wrongdoing. Algorithmic governmentality may well be a new form of structural sin—because it can lock in inequality, amplify bias, and obscure accountability.

To read prophetically is to:

- Reveal what the system hides.

- Defend those most harmed (those whose data is exploited without consent, or whose access is restricted by algorithmic sorting).

- Call for transparency, justice, and accountability from platform builders.

This is the prophetic task: not just to understand power, but to demand the repentance of unjust systems.

A Concrete Example: When Algorithms Decide Lives

Consider a simple case: algorithm-based social assistance distribution. In some countries, governments use digital data to determine eligibility for aid. Algorithms are praised for their efficiency. Yet on the ground, some citizens lose aid because their data is incomplete or misread.

Who is responsible? The field officer? The programmer who wrote the code? The minister who signed the policy? The answer is often unclear—this is the very problem of the “faceless tyrant” that Rouvroy critiques.

Prophetic critique would say: technology may be efficient, but it must also be just. Decisions affecting human lives cannot be hidden in a black box that no one can question.

The Way Forward: Prophetic Literacy

Facing algorithmic power, it is not enough to be “smart consumers.” We need to develop prophetic literacy: the ability to read technology with critical eyes and justice-oriented hearts.

Some first steps might include:

- Community education. Churches, schools, and civic groups can host digital literacy classes explaining how algorithms work and their social impact.

- Simple audits. Communities can observe how platforms influence thinking and behavior (e.g., whether news feeds are polarizing members).

- Policy advocacy. Demand regulations that ensure algorithmic transparency and user privacy protection.

- Spiritual practice. Encourage digital detox, intentional breaks from algorithmic feeds, and exercises that reawaken free decision-making.

This way, digital ideology critique is not just theory but concrete action helping society live more justly in a data-driven world.

Conclusion: A Prophetic Call for the Digital Age

From Foucault, we learn that modern power organizes life; from Rouvroy, we learn that in the digital age, power becomes automated and predictive. But we cannot stop there.

Prophetic critique calls us to speak—even against the flow—for those who have no voice. In an era where algorithms decide what we see, we must seek truth that is not pre-selected for us. In an age of prediction, we must defend the unpredictable: freedom, justice, and love.

Perhaps our task today resembles that of the ancient prophets: to denounce the “idols” of our age—blind faith in technological neutrality. Algorithms can be good tools, but they are not the ultimate arbiters of life. With critical awareness and prophetic courage, we can re-shape the digital world so that it serves humanity rather than enslaving it.

References

- Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Rouvroy, A. (2021). “Algorithmic Governmentality: Understanding the Power of Algorithms.” In Critical Data Studies Reader.

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs.

- Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.

- Couldry, N. & Mejias, U. (2019). The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. New York: Crown.